THE ART OF DYING: Writings, 2019-2022, by Peter Schjeldahl

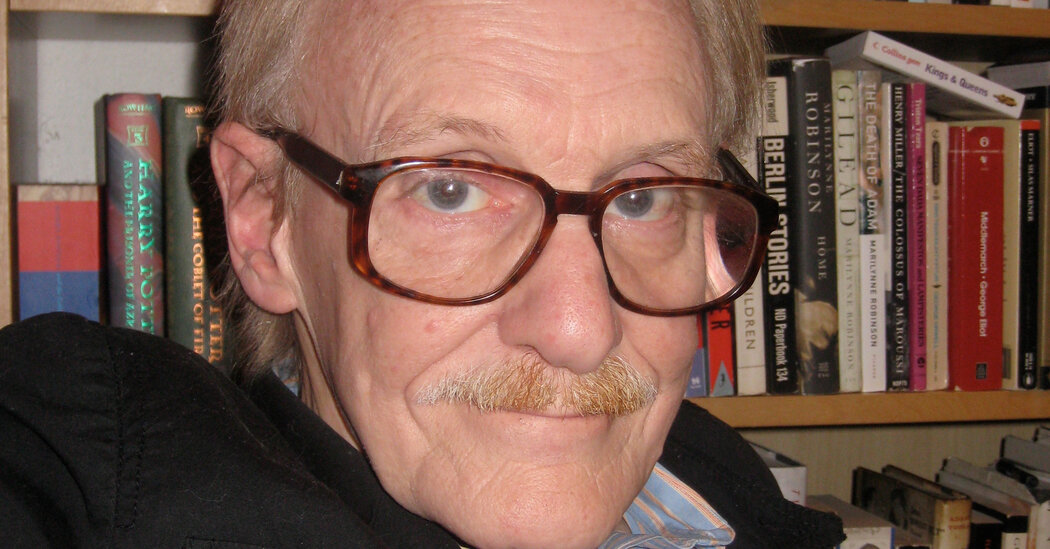

One day in 2019 the art critic Peter Schjeldahl was rushing to catch a bus. He leaped over a chunk of broken asphalt, caught a toe and fell. His glasses were smashed; there was blood. He was taken to an emergency room in Greenwich Village.

A CT scan, intended to check for neck injuries, revealed a spot on his left lung. Not long after, an oncologist told him he had six months to live. He beat that diagnosis and died four years later, in the fall of 2022.

Schjeldahl’s sensitive and moving new book, “The Art of Dying: Writings 2019-2022,” collects his final essays and reviews. It has two distinct parts. The first is the stark and droll title essay, which caused a sensation when it was published in The New Yorker in 2019. The second and larger part comprises the increasingly personal and plain-spoken art reviews he continued to write for that magazine.

Like Karl Marx and Jim Harrison, who died at their desks, and George Orwell, who was writing a book review when he died, Schjeldahl wrote until the end. We can be grateful for that because we have this book.

Like you, perhaps, I’ve read Schjeldahl’s art criticism for decades, first in The Village Voice and then in The New Yorker, where he became head art critic in 1998. Along with Time magazine’s mercurial art critic Robert Hughes, he taught me how to see. Schjeldahl’s tone was shrewd but rumpled and bohemian. It wore well over time.

He was a reliable dispenser of epigrams, a quality he did not lose after his cancer diagnosis. Here are a few sentences from his new book:

I swatted a fly the other day and thought, Outlived you.

If people praising you knew the half of it, they’d think twice.

A thing about dying is that you can’t consult anyone who has done it.

He’s Donald Judd; you’re not.

The less you see, the dumber you get.

Writing is hard, or everyone would do it.

Loving art always involves catching up to ourselves.

If I were paid by the word for this review, I would (and could) keep going.

This collection’s title essay has been widely discussed. Read it if you haven’t. His private life has been pored over as well. Upon his death there were many obituaries and appraisals. Not all the press was positive. His daughter, Ada Calhoun, published a well-received memoir, “Also a Poet,” in 2022. It had much to say about his distracted, substandard, “safety third” parenting style.

Given all this, let’s consider Schjeldahl’s final art reviews. There are 45 of them here. Most are Covid pieces, of a sort. Like the rest of us, he was trapped indoors, hunkered down, mostly in the home he and his wife owned in the upper Catskills. Galleries were closed. He reviewed at least one show from its catalog.

He was depressed. He definitely did not quit smoking. “Quit now?” he wrote. “Sure, and have the rest of my life be a tragicomedy of nicotine withdrawal.”

Finally allowed back into galleries, it was as if Schjeldahl had corneal transplants. He was ambushed by beauty, and he transmits that wide-open feeling. Walking into the Frick for the first time in ages, he felt he was coming home.

The misanthrope in him did miss face masks. He dug these because they reduced “unsought conversation.” They also hid his “chagrin at failing to recognize people who did address me. (‘Good to see you’ goes only so far.)”

The surest sign that someone has genuine taste, Auden wrote, is that they’re uncertain of it. Auden could have been talking about Schjeldahl. He buffs and revises many past opinions. “I remember hating those on my first sight of them,” he said about Gerhard Richter’s chromatic abstractions, before finding them “miraculously, often staggeringly, beautiful.” He calls Richter’s 1988 portrait of his daughter Betty, her upper body seen from behind, as “the single most beautiful painting made by anyone in the last half century.”

He was slow, he admits, to come around to Philip Guston’s work. He recalls actively disliking Andy Goldsworthy’s snaking stone wall at Storm King. Now he finds it “rigorously intelligent as well as ecstatic.” Goldsworthy’s formidable but mischievous wall is among my own favorite works of art.

The late Schjeldahl was a lover not a fighter. His highest praise? It was to admit he wanted to steal certain paintings. About one of Mondrian’s “plus and minus” paintings, he wrote, “I want one!” Sometimes he did open his wallet. “Writing a check is intrinsically more sincere than writing a review, because the expense hurts,” he wrote.

There are few entrails on the floor of this book. But Schjeldahl did not become utterly toothless. He was no fan of J.M.W. Turner, or the artist and designer Kaws. Andres Serrano’s “Piss Christ” was “puerile.” He had no special fondness for Marcel Duchamp. The work of the Russian artist El Lissitzky was “annoying.”

He was unsure what to make of the 2022 Whitney Biennial. He liked a lot of what he saw, while noting the show’s “overt embrace of identity politics” and its plethora of styles “that have yet to demonstrate staying power.” “Hating the Biennial is practically a civic duty, or a pledge of un-allegiance,” he wrote. He didn’t hate this one.

The Biennial review is a reminder that Schjeldahl exited lockdown into a world transformed by new social and political forces, including Black Lives Matter. Art fueled by these forces could be galvanizing, by braving the “routine chaos” of the world, but it was too often predictable and prescriptive. “Must ideology define us?” he asked, in a review of another show dominated by political themes. “Can we demur from one extreme without implicitly being lumped in with its opposite?”

In a short story titled “Café Loup,” Ben Lerner wrote, “Nothing is a cliché when you’re dying.” You feel that in these reviews. “I’ve been feeling apologetic to certain trees, near my home,” Schjeldahl wrote, “for my past indifference to their beauty.”

He was especially taken with one of the great Helen Levitt’s street photographs, a scene of three boys play-fighting that channels “millennia of human experience.” It was something to hang his tattered soul on. He wrote, “I can still see it with my eyes closed.”

THE ART OF DYING: Writings, 2019-2022 | By Peter Schjeldahl | Abrams | 284 pp. | $30