Then in the 2023 documentary “Joan Baez I Am Noise,” the former Belmont resident revealed her diagnosis of dissociative identity disorder, a coping mechanism after burying childhood abuse by her father.

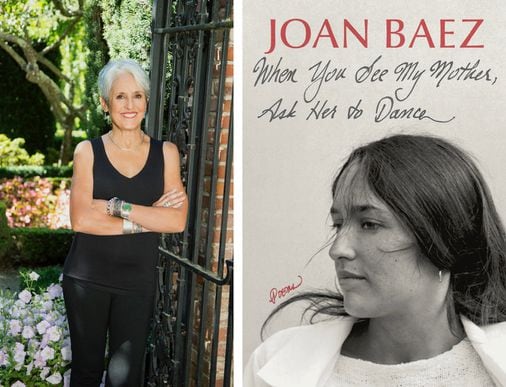

But it is in her 2024 debut book of poetry, “When You See My Mother, Ask Her to Dance,” published by Boston’s Godine, that she introduced us to some “alters,” a word Baez uses in our interview for lack of a better term.

In a candid author’s note, Baez, gets right to it: “In 1990 I began therapy that led to a diagnosis of dissociative identity disorder. That’s clinical-speak for developing multiple personalities as a way of coping with long-term trauma.” Some poems “are heavily influenced by, or in effect written by, some of the inner authors.”

You’ll notice some bylines: “The Rosy Trumpeteers,” by Yasha, or “Star: A Revery,” by Star, and “Queen of the Mountain,” by B.B. and others. One poem, to Leonard Cohen, is credited to both Baez and Yasha.

The book is powerful and eye-opening, and beyond being revelatory, plenty of it is just plain good poetry.

When I ask about a poem written for her son, Gabe, she tells me: “Some of the poetry, I’m happy to say, was written later, and wasn’t just by somebody in there. I need to know that, if I want to do any more poetry. That it has to be me.”

When her father, Albert, was a professor at MIT, Baez lived in Belmont and performed in the Cambridge folk scene, notably at Club 47 (now Club Passim). She’s been a Newport Folk favorite since 1959.

We spoke ahead of her appearance Saturday at the festival, where she will read some of her poems. We talked about her diagnosis, her childhood, Bob Dylan, and forgiveness.

You were diagnosed in 1990. Had you been in therapy prior?

Since I was 15. A string of really good therapists helped me get around, over, and under the issue. It wasn’t until I was 50 that I was willing to dig deep. I knew something was off by a mile, but I didn’t know what it was. So a lot of it comes out in the poems, and poems written by alters — it’s a stupid word, but the people within me.

“Goodbye to the Black and White Ball,” feels like a thesis statement. What sparked that?

It all got sparked by the same thing: the revelations I was going through. It was painful, of course, but not as painful as the years leading up to it, things I had to deal with, not understanding what was wrong with me. I’m sure there are many in that same boat. My encouragement is: All the stuff I did in therapy — some radical — was less painful and scary than what I’d lived through.

It’s important that you’re talking about this now. Airing these stories can be important for others to read.

The more they’re aired, the more people are able to say, “She lived through it. I can live through it.”

Do you remember when Miss America came out, a long time ago, that her father had raped her, and the word incest was used for the first time, I think, publicly? [In 1991, Marilyn Van Derbur, Miss America 1958, made her story public.] I thought she was very brave. She had no #MeToo movement to back her up. I’d credit some of my thinking and courage to her.

“In My Day” feels like it’s dealing with generational trauma.

It has to be generational. Something terrible must’ve happened to my father.

Being split myself, I can understand. I don’t remember what happened here or there. I suddenly thought, “Oh, my God, my father must have been a multiple.” If he split to do this stuff and then came back as a sort of a shining professor and lovely guy — which he was — and not remembering what he’d done the night before.

You say you don’t remember spots, and your parents remember nothing.

Right. I mean, I remembered nothing until I was 50, and went looking for it.

In “Nowadays,” written for “my father in his 93rd year,” you recall watching him swim. You write: This was me/ overflowing with love.

In those moments, there’s nothing in here except forgiveness. I’m lucky because some people are furious for the rest of their lives and never forgive their parents.

You blocked memories out, and started digging after your sister Mimi called you.

Yeah. I felt hair go up on the back of my neck when she said, “I have some memories about Popsy,” our father. She was the first one to figure it out.

You’d been in therapy since you were a kid, but it sounds like after that call, therapy changed.

The lid blew off. I’d been holding it together because of good therapists. They’d get me from one concert to the next. They must’ve known something crazier was going on, but none of them knew what because I couldn’t give them any hints.

You have bylines for Yasha, Star, B.B. Yasha co-writes “Dear Leonard” for Leonard Cohen.

Yasha was the best poet I ever had in here. He appeared really vividly. I was listening to Leonard Cohen. I saw this little boy trying to climb uphill in a snowstorm. Then he starts writing. I was blown away.

You write that Yasha is 12, and lost his parents in the Holocaust. So when you saw him, he had a backstory.

That’s a good way to put it.

What about Star?

She’s much livelier and came later. B.B. didn’t want to get older.

You have “Portrait” for Bob Dylan. You said you had to let go of some resentment.

I was painting him and had an epiphany. I put on his music and wept for about 24 hours and washed out any resentment that was left. It was extraordinary. All that angst and bitterness disappeared over that 24 hours. I was thrilled. That was probably eight years ago.

The title poem is written for your mother and Swedish tenor Jussi Björling.

My mom [loved] his voice. I did, too. He remains my favorite opera tenor. There are many more bombastic, or better actors — but this one had tears when he sang.

Interview was edited and condensed. Lauren Daley can be reached at ldaley33@gmail.com. She tweets @laurendaley1.

Lauren Daley can be reached at ldaley33@gmail.com. Follow her on Twitter @laurendaley1.