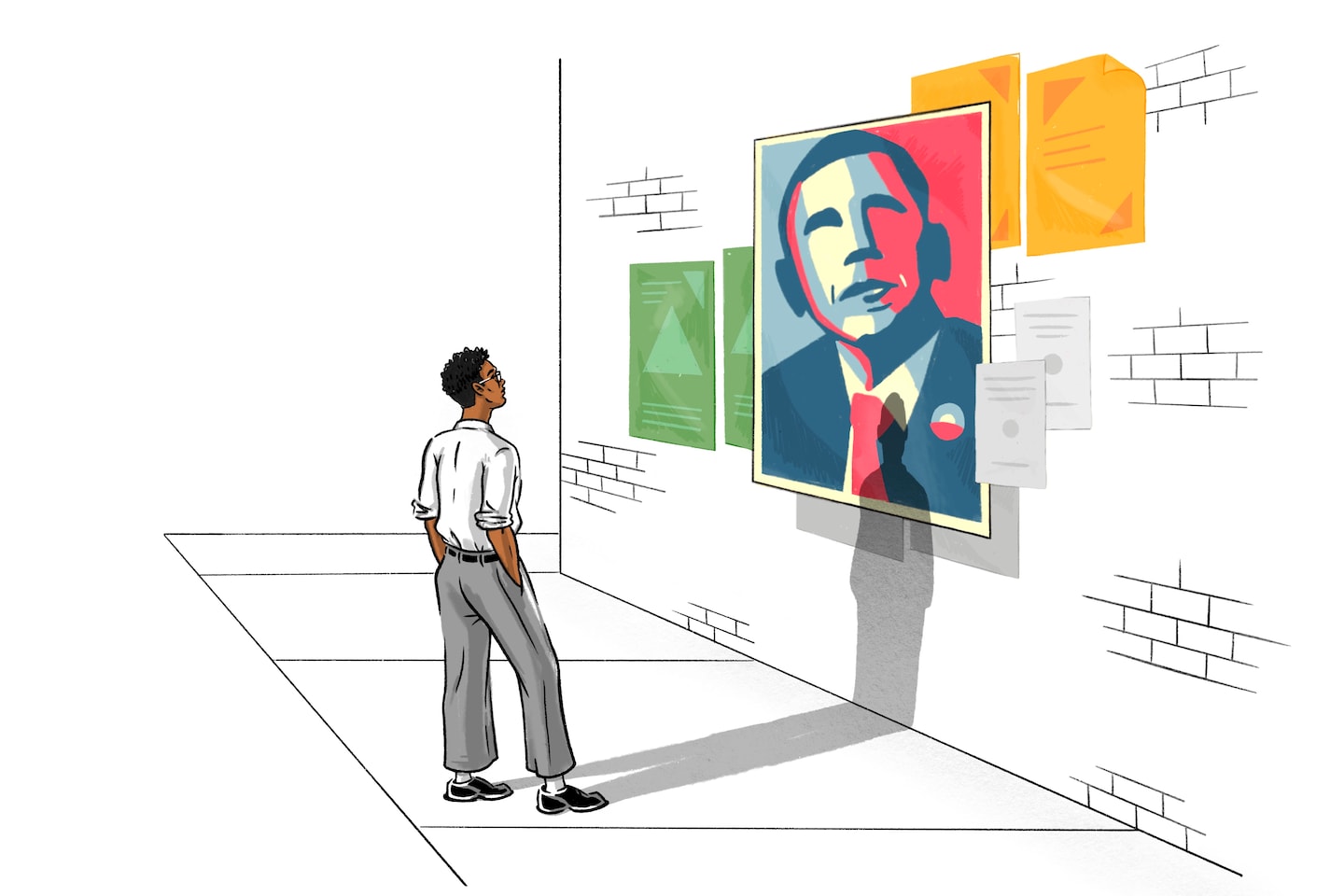

Vinson Cunningham, a former assistant in the Obama White House, subverts that sly mystery. “Great Expectations,” his boldly titled debut novel about a presidential campaign, proclaims Cunningham’s name but never names the candidate. Considering how specifically Obama is described in these pages, readers may find that omission cute, but it’s more than that. There’s a prevailing sense in “Great Expectations” that the eloquent Black politician from Illinois, “projecting an intimacy that was more astral than real,” is too indeterminate to be named. He’s a Rorschach test for America.

The first time “the Senator” appears in these pages — in 2007 during “a reception at a music producer’s apartment” — the room reorients itself around the candidate’s magnetism. Cunningham, a drama critic at the New Yorker, immediately demonstrates how attentive he is to the mannered theatricality of politics and particularly to Obama’s dramatic persona:

“His height was helped by an incredibly erect posture that looked almost practiced, the kind of talismanic maneuver meant to send forth subliminal messages about confidence and power. In the same way, and engendering the same effect, he held his chin at a high angle, aimed not directly ahead but at a point on the ceiling several yards ahead.”

This narrator, who wields talismanic maneuvers of his own, is David Hammond. He’s a bright young man who fathered a child and flunked out of college. After a year fumbling around in the wreckage of his great expectations, he began tutoring the son of a wealthy, politically connected woman, and by some fluke, that led to a job as a lowly fundraising assistant with the Senator’s presidential campaign. He quickly discovers he has a natural facility for soliciting donations from well-heeled Democrats.

The theme of money’s role in American politics may feel as fresh as a battered suitcase of unmarked bills, but the story of “diligently harvested cash” is merely background music for this novel. At 22, David is given entree to a world of rap stars, Wall Street bankers and high-society liberals who party in mansions on Park Avenue where the candidate’s appeal to common folk is debated with rising optimism.

“Everything that happened in my life, good or bad, seemed to be an accident,” David says. “I’d somehow groped my way to the middle of the world. The middle of a world, at least. Or an unseen perch quite near the center, with an excellent view.”

But despite the novel’s steady drip of astute observations about Obama and his groundbreaking campaign, the excellent view David gives us is relentlessly introspective. He has a very personal reason to keep his eye on the people engineering the Senator’s victory: “I watched them closely,” he confesses, “searching for a way to be.”

How to be — or not to be — that is the question David mulls throughout this meditative novel that periodically checks in at well-known mile markers along Obama’s march toward the White House. In the context of this political revolution, that fixation on a lowly fundraising assistant could feel misplaced, even forced. Indeed, with an intensely ruminative protagonist — unmarried, without a degree, struggling to figure out how to be a father, jumping from one temporary career to another — “Great Expectations” risks sliding into the Audacity of Mope. But it’s wholly redeemed from that fate by how elegantly Cunningham explores the mind of this young Black man struggling to divine his role in a nation woven from money and faith.

David may have failed his college classes, but he clearly did all the reading — even the supplementary reading that no one does. Listening to the Senator speak to a crowd of rich donors, he’s reminded of a character from Henry James’s “The Bostonians.” Watching the Senator walk briskly outside, he likens him to “Whitman over Brooklyn’s ‘ample hills.’” Allusions to Ralph Ellison, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Dorothy West, Toni Morrison and others continually sprinkle down on these pages like holy water.

But no book is referenced here more frequently than the Bible. No other recent American novelist, except perhaps Marilynne Robinson, contends so diligently and so textually with the function of Christianity in the United States. Cunningham signals that engagement immediately when the novel opens with an analysis of the candidate’s sermonic oration. “The Senator had begun, even then, at the outset of his campaign,” David says, “to understand his supporters, however small their number at that point, as congregants, as members of a mystical body, their bonds invisible but real.” Without sounding ecclesiastical or like “some nationalist-imperialist pervert,” the Senator manages to reach back to the earliest manifestations of America’s spiritual mythology. “Despite his references, overt and otherwise, to Lincoln — and, more gingerly, to King — his closer resemblance was to John Winthrop making phrases on the ship Arbella, assuring his fellow travelers that the religion by whose light they’d left Europe in 1630 could cross spheres, from the personally salvific to the civic and concrete.”

David may have crossed from belief to unbelief, but as a young man raised in the fire of a Pentecostal church and educated by Jesuits, he still reads the world around him through the scrim of Scripture. You can hear that even in his grammar, the way he constantly interrupts himself, corrects himself, drills down again and again to some further explication.

This is the kind of novel — is there such a kind? — in which the subject of “the Bible’s hermeneutic density” is considered in some detail. Taking a ferry to a fundraiser on Martha’s Vineyard, for instance, David slips effortlessly into a discussion of water in the Old Testament and the Gospels. His reflection on the story of Nicodemus questioning Jesus is delivered with the sort of intellectual depth, spiritual insight and sincere humility that could draw me back to church.

In David’s framing, the campaign is missionary work, the accommodations marked by “monkish austerity,” the rewards not of this world. Unshakable belief is an office requirement. The candidate is Christ; the fieldworkers John the Baptist. “We fundraisers,” David says, “trussed up our devotion in business attire, semi-terrestrial office hours, and a focus on numbers instead of individual hearts: so many high-church smells and bells, aimed not so secretly at assimilation into the wider culture toward whose transformation the effort was aimed.”

In a nation riven by theology, we’ve long been ill-served by literary fiction that remains locked in a reductive dichotomy of belief vs. doubt or, worse, simply pretends that religion doesn’t exist. Cunningham’s great accomplishment in this gracefully written novel is to demonstrate how the religious mind-set persists outside of parochial devotion, how the language of Scripture, the grammar of faith, shapes our experience even after the spirit seems to have left the body politic. The result is a coming-of-age story that not only captures the soul of America but also feels the unquenchable thirst for meaning which passeth all understanding.

Ron Charles reviews books and writes the Book Club newsletter for The Washington Post.

Great Expectations

Correction: An earlier version of this review misspelled the narrator’s last name. It is Hammond, not Hammons. This version has been corrected.