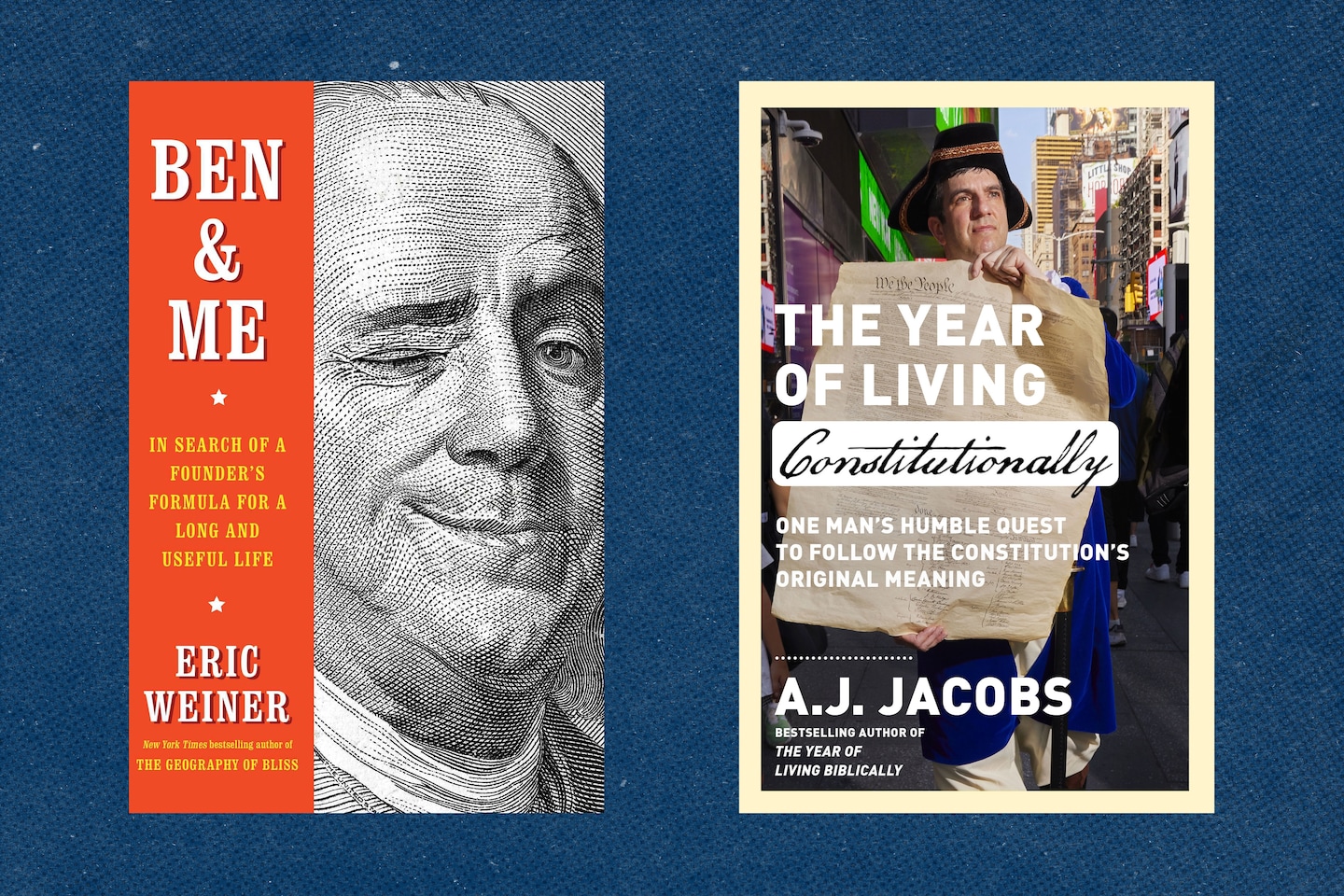

Two humorous new books probe these conflicting attitudes while warning of the perils of simplistic, binary thinking. What do their authors think we might still learn from the Founders — and from the Constitution those men entrusted so hopefully to posterity?

A.J. Jacobs, in “The Year of Living Constitutionally,” is initially dubious. “Should we be skeptical of this set of rules written by wealthy racists who thought tobacco-smoke enemas were cutting-edge medicine?” he asks. Surely yes …?

His method for assessing the continuing utility of the Constitution is to “get inside the minds of the Founding Fathers.” Jacobs wants to be “the original originalist” — that is, to follow the doctrine of constitutional interpretation that favors the semantic and political frameworks prevalent at the time it was written. Armed with a tricorn hat, goose quill pen and a large supply of candles, he does his best to live 1790s style and exercise his Constitution-given rights, whether it be carrying a musket, quartering a soldier, or gaining a letter of marque and reprisal and becoming a privateer. What larks.

Jacobs’s gonzo approach, while occasionally silly, is not ineffective. In testing the Constitution’s more outdated elements, he shows how stupid it can be to take 237-year-old rules literally. And he backs his stunts with research and interviews with academics to get an even more alarming sense of the implications of originalist thinking. I was surprised to discover that even the clearly worded rights listed in the First Amendment were interpreted radically differently in the late 18th century. Anti-cursing laws, statutes banning theater and the imprisonment of members of Congress for dissent were all basically kosher — imagine!

Jacobs’s point isn’t that the Founders were maniacs or that we should ditch the Bill of Rights. Rather he’s building a case for living constitutionalism, the philosophy that the founding documents’ basic tenets can remain a guide even as society and technology change. At a time when a majority on the Supreme Court favors its opposite, originalism (at least when convenient), and is actively attacking freedoms such as reproductive rights and the power of federal agencies to protect the environment, it’s vital to question the philosophical underpinnings of their approach. Jacobs seems to me essentially correct in calling the Constitution “a national Rorschach test.” We see what we want to see; the idea of a definitive interpretation should be treated with suspicion.

In any case, the text of the Constitution was arrived at only through bitter debate. Part of the reason so much of it hums with ambiguity and requires specialist interpretation is because the delegates at 1787’s Constitutional Convention couldn’t agree what to put in it and were forced to compromise. Only after four sweltering months in Philadelphia did they arrive at a draft they could live with. Benjamin Franklin spoke for many of the delegates when he declared at the end of the convention, “I confess that I do not entirely approve of this Constitution.” Nevertheless, he added: “I doubt too whether any other Convention we can obtain, may be able to make a better Constitution.”

Franklin is the subject of Eric Weiner’s book “Ben & Me: In Search of a Founder’s Formula for a Long and Useful Life.” Weiner, like Jacobs, searches in the past for guidance on how we should live now and finds, in Renaissance man Franklin, an inspiring example.

Among his many admirable qualities, per Weiner, were his stoicism and the “modest diffidence” (Franklin’s words) he practiced in conversation and debate — in stark contrast with today’s feral hyperpartisanship. These are, of course, also among the essential tools of diplomacy, and luckily, when his country was in direst need, Franklin was at the height of his powers. If you saw “Franklin” on Apple TV, with a twinkly Michael Douglas charming the powdered wigs off French aristocrats, you’ll be familiar with the critical diplomatic feats he executed during the Revolutionary War.

While there’s much to admire about Franklin, he was also one of the aforementioned slaveholding Founders. Indeed it took him till 1785 to emancipate his last enslaved person. Weiner ties himself in knots trying to demonstrate, through Franklin’s writings, the gradual shift in his thinking, but it certainly took him a while to become the “all-in abolitionist” Weiner describes. Nevertheless, he did change his position, eventually becoming president of a notable abolitionist society, and his evolution on the subject is suggestive of one final virtue. “At a time when opinions have calcified,” Weiner writes, “Franklin reminds us that changing your mind is not only a noble act; it is also an American one.”

Though there are unignorable limitations in mining the early republic for guidance, there’s still plenty to learn from the past. Though Weiner focuses largely on Franklin, the lives of most Founding Fathers illustrate a certain mutability of intention and ideology. And this is good! Flexibility and willingness to compromise are desirable qualities in politicians, especially in an era of chronic entrenchment and bitter division.

As for the Constitution, that which lasts always has at least a kernel of goodness in it, and the Founders’ greatest hit has many. Jacobs, like many before him, particularly admires its capacity to change. Though the amendment process is difficult, the passage of 27 amendments since 1787 shows, for the most part, how the Constitution might be incrementally improved, through consensus-building, without having to start from scratch. Progress may be intermittent, but it accrues.

Originalism, however, impedes progress and must be subject to thorough scrutiny. Even the Founders were wary of it: No less a man than Thomas Jefferson argued that “laws and institutions must go hand in hand with the progress of the human mind.” This view has been inherited by all who believe that a living Constitution can still offer hope. These include the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., who saw it as a “promissory note to which every American was to fall heir,” Thurgood Marshall, who had no illusions about its imperfections but fought tirelessly to deliver greater justice through its provisions, and President Barack Obama, who used the Founders’ words to speak hopefully of the promise of “a more perfect union.” This feels like a good way to look at the past: not just with a clear sense of right and wrong but also a desire to build on, not destroy, what the Founders started.

Charles Arrowsmith is based in New York and writes about books, films and music.

The Year of Living Constitutionally

One Man’s Humble Quest to Follow the Constitution’s Original Meaning

In Search of a Founder’s Formula for a Long and Useful Life

Avid Reader Press. 336 pp. $29.99