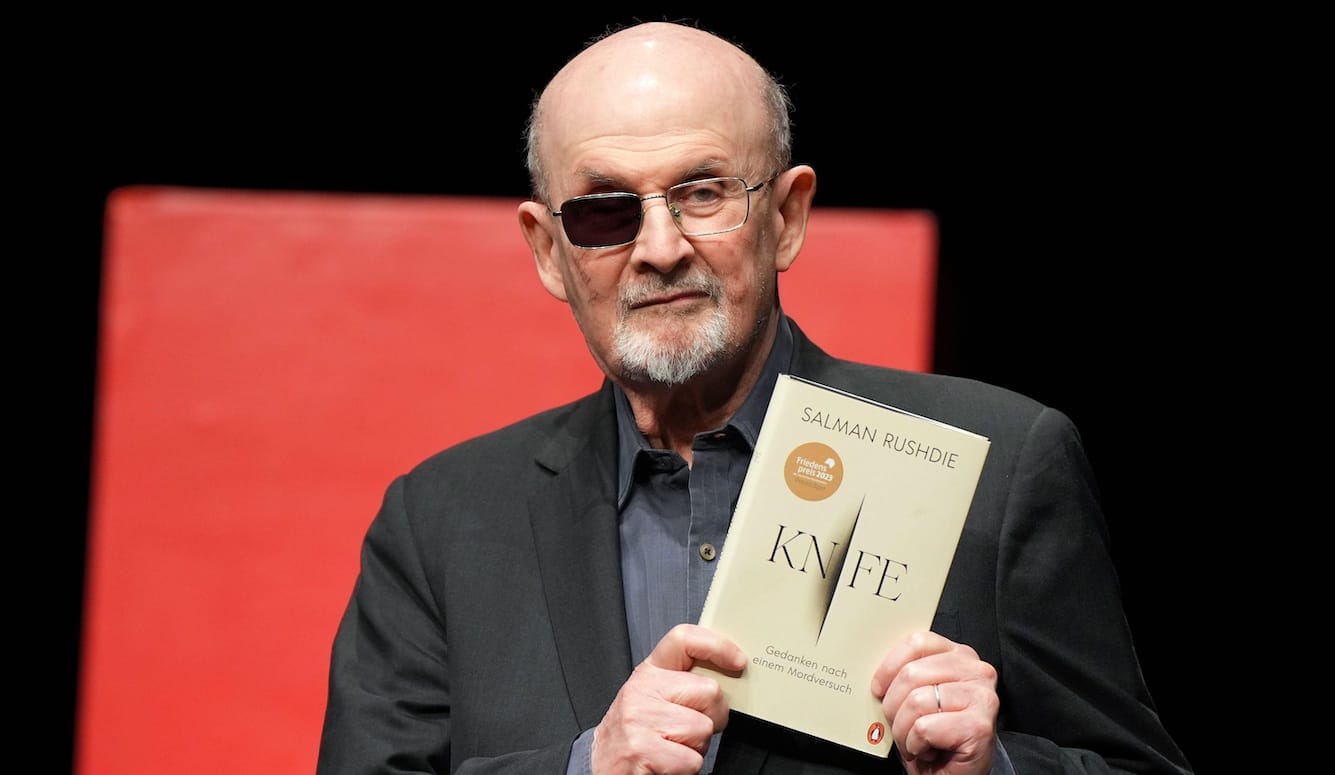

A review of Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder by Salman Rushdie, 209 pages, New York: Random House (April 2024)

My copy of Salman Rushdie’s new book, Knife, arrived a few weeks ago, and before I had even opened the package, the news also arrived that Paul Auster had succumbed to cancer—and the confluence of Rushdie’s book and the information about Auster hit me harder than I would have predicted. Rushdie and Auster were friends. I knew this because in August 2022 there was a major assassination attempt on Rushdie—the assassination attempt is the topic of Knife—and a very few days later PEN America, the writers’ organisation, held a solidarity rally on the steps of the 42nd Street Library in New York. I attended, and I listened to Auster deliver a short speech. He celebrated Rushdie’s dedication to the storytelling imagination. He conjured the principle of freedom, and, in doing so, he expressed quietly an ardour of personal love, one friend for another in his moment of extreme trouble.

But it is Auster who has died, and the news has led me just now to reflect on the death, as well, of Rushdie’s close friend Martin Amis, who likewise succumbed to cancer, a year ago; and on the death thirteen years ago, again of cancer, of Amis’s best friend, Christopher Hitchens, the journalist, who was Rushdie’s friend as well. So I found myself gazing ruefully at the package with Rushdie’s book inside, and I was hit with the recognition that an entire chapter of Anglo-American letters appears to be nearly at an end—not entirely, of course, given that Rushdie does, in fact, have a new book. But his book is nothing if not a contemplation of mortality.

Perhaps it is less than appropriate to associate Auster with those other writers. Rushdie, Amis, and Hitchens took their first steps into the literary world under English skies, and they embraced a new existence in the far-away United States only later in life. Auster, by contrast, was a New Jersey boy whose own journey carried him across New York harbour to Columbia University and thence to Brooklyn, which was merely a commute. And his imagination always seemed to draw on the French, more than on the English.

Still, one of Auster’s books conjures, in a New Jersey and New York version, an atmosphere that shaped all of those people. This is his 900-page digitally titled novel 4 3 2 1, which recounts the progress of a New Jersey boy from high school to involvement in the 1968 student uprising at Columbia University. Nothing that happened among students in the United Kingdom in and around 1968 proved to be quite as riotous or imposing as the uprising at Columbia that year. And yet, the spirit of insurrection was more than American, and Rushdie, Amis, and Hitchens came of age breathing its vapours quite as much as did Auster in New York. And in one respect, all of those people responded in the same way, which was by cultivating a dandy exuberance in their prose, happy to attract attention to its own virtuosity.

In the Country of Last Things

A look back at the work and impressively productive life of Brooklyn’s most famous resident, Paul Auster.

This was the prose of writers for whom ebullience itself was a generational rebellion (as it was for a number of writers in France, as well). In Auster’s case, ebullience sometimes meant the construction of vast sentences, curling elegantly from one page to the next. And Rushdie, too, has made himself the master of the run-on and the strung-together, bubbling with delight at a colourful world and his ability to conjure it—not that Rushdie’s jolly and boisterous extravagances sound even remotely like Auster’s smooth complexities.

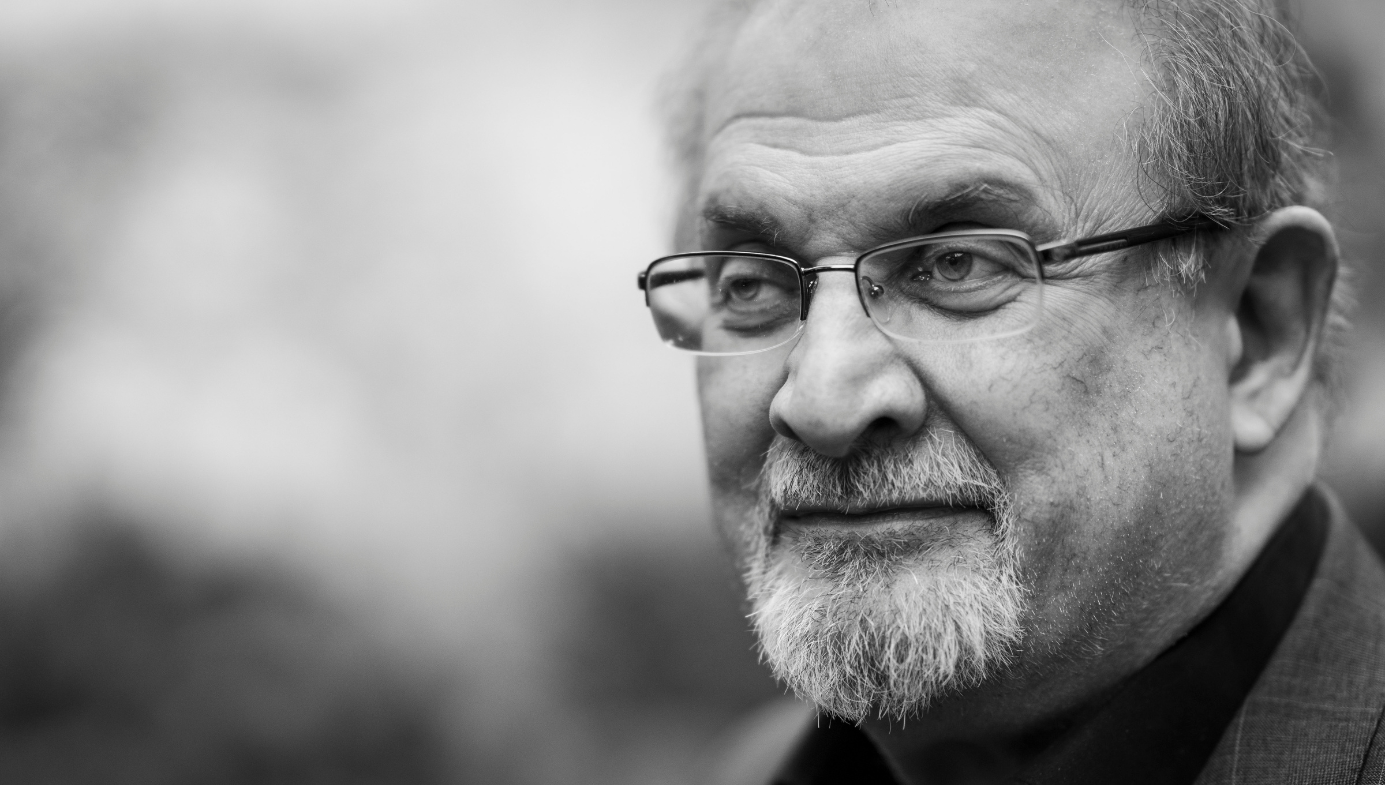

So three of that little group are gone, and the last man standing turns out to be Rushdie, which can only have left the god of actuarial probabilities, if such a deity exists, puzzled. Rushdie reflects on this in Knife: “There have been many times since the attack when I have thought that Death was hovering over the wrong people. Wasn’t I the one earmarked for collection by the Reaper, the one about whom everyone agreed that the odds were strongly against my surviving?” And yet Death was, in fact, hovering over Rushdie, too, even if, when it went in for the kill, some other fate or deity or happenstance chose to intervene.

The man who attacked Rushdie was—as he explains in Knife—a young person from a Lebanese Shiite background in New Jersey, who had visited the family home in Lebanon and returned to New Jersey in a tither of Islamist radicalisation. Rushdie was scheduled to speak at a legendary literary-and-ideas festival in the upstate New York town of Chautauqua. He took his place on the stage. And the young man from New Jersey, who knew barely anything about Rushdie, except that Ayatollah Khomeini had denounced him as an enemy of Islam worthy of death, raced down the amphitheatre aisle dressed in black, which is how one terrorist after another has outfitted himself on the occasion of a martyrdom operation.

In the introductory chapter of Knife, Rushdie offers a description of what happened next that he calls a collage, consisting of bits of his own memory, together with what other people have reported. The collage is shocking. I will quote it more than minimally because, very unfortunately, in order to understand Rushdie and what he has done in Knife and in other books as well, you have to register some small part of the shock yourself:

At first I thought I’d just been hit by someone who really packed a punch. (I learned later that he had been taking boxing lessons.) Now I know there was a knife in that fist. Blood began to pour out of my neck. I became aware, as I fell, of liquid splashing onto my shirt.

A number of things then happened very fast, And I can’t be certain of the sequence. There was the deep knife wound in my left hand, which severed all the tendons and most of the nerves. There were at least two more deep stab wounds in my neck—one slash right across it and more on the right side—and another farther up my face, also on the right. If I look at my chest now, I see a line of wounds down the center, two more slashes on the lower right side, and a cut on my upper right thigh. And there’s a wound on the left side of my mouth, and there was one along my hairline too.

And there was the knife in the eye. That was the cruelest blow, and it was a deep wound. The blade went in all the way to the optic nerve, which meant there would be no possibility of saving the vision. It was gone.

He was just stabbing wildly, stabbing and slashing, the knife flailing at me as if it had a life of its own, and I was falling backward….

Rushdie explains that he was lifted onto a stretcher and a gurney and carried to a helicopter, which brought him to the closest hospital capable of dealing with wounds of that severity. Teams of doctors were far from confident of success in rescuing their patient. Then a further journey to Manhattan and still more doctors and nurses and a physical therapist, who inflicted a lot of pain on his hand, which turned out to be good for the hand. But the additionally terrible thing, as you discover all this in the pages of Knife, is to reflect that everything he experienced in the Chautauqua attack and its painful aftermath in the hospitals was at one with his life as a whole, ever since the ayatollah’s original fatwa back in 1989. Rushdie tells us that, in the years after the fatwa, the British police foiled six assassination attempts against him. He refrains from making a thorough tally of other plots, directed against his publishers and translators in other countries, that were not, in fact, foiled, but he says enough to make us reflect on this ourselves. He does remind us of the attack on Naguib Mahfouz, the Egyptian novelist and Nobel Prize-winner, in 1994, which, in Rushdie’s view, was one more violent act in the larger wave of violence that was set off by the ayatollah’s fatwa.

He reminds us of how much disdain and contempt came his way in the United Kingdom during those next years—the response to him by people who, instead of seeing in The Satanic Verses a serious and imaginative exploration of mental disorder and the blasphemy that is Islamist extremism, preferred to see in it a reprehensible goading of respectable piety. He reflects on how awful it was for him to recognise that entire publics among the South Asians, both in their British diaspora and in the South Asian countries themselves, came to revile him; how awful it was for him to become, in the imagination of immense populations, a demonic figure; how awful to endure decade after decade of that sort of loathing, only to have the loathing culminate in the attack itself.

I do not mean to suggest that, in reflecting on all this in the pages of Knife, Rushdie falls into a stupor of self-pity. He tells us that, as part of his recovery in New York, he visited his psychotherapist and said that he did not want to complain—only to have the psychotherapist observe that complaining is the whole point of psychotherapy. So he does allow himself to complain. He remarks that his surviving eye has not been in such great shape either, and for several years now he has had to submit to monthly injections in the white of the eye. But he dwells on his physical sufferings only for so long, and something is touching in the combination of reason to complain and reluctance to complain.

And then, having elaborated on his sufferings as much as he cares to do, he recounts the factors that have allowed him to survive—the personal factors, apart from the help given to him by his fellow-participants at the Chautauqua event, who leapt to his aid, and the police, who did not leap to his aid, but did eventually arrive, and the medical teams. His wife, who for the last several years has been the poet Rachel Eliza Griffiths, proved to be much superior in wifedom to at least a couple of his previous wives (there have been five altogether), whom readers may recall with amusement from an earlier memoir, Joseph Anton. The wife’s own family rallied to his side. His sister and his son in the UK made their way to him, and a circle of people who, like Auster and Rushdie’s loyal agent, Andrew Wylie, similarly found one way or another to lend him moral support, or lend him an apartment hideaway, or hire an airplane.

But he reflects on his internal strengths and resorts, as well, and these turn out to be elements of his literary vocation. Dostoevsky in Russia in the mid-19th century was arrested and imprisoned as a militant of the anti-tsarist cause, and, though without getting physically attacked, was subjected to a moment of absolute terror—taken from his cell to be shot, given last rites, and only then, in front of the firing squad, informed that his execution was a prank of the tsar, intended merely to rattle him. And Dostoevsky, too, looked to his literary vocation for a response. Only, Dostoevsky’s response consisted of sinking into ever deeper anger, no longer confined to an indignation at the injustices of the tsarist system but now directed at falsities of every sort, including the falsities of the anti-tsarists, and the falsities of human nature, and the falsities and truths of the human contemplation of God. Dostoevsky responded, in sum, by changing. He darkened.

But Rushdie’s response, as he makes clear in Knife, was to refuse to change, and to do so as a matter of defiance, in plain evidence that odious threats from the ayatollah and his vast public were not going to mould the contours of his own imagination. Happiness, he explains, has always been his ideal and principle—happiness in his personal existence, and in the pleasure that he takes in literature. So he chose to stand by happiness. But what is happiness for Rushdie? I take it from Knife that happiness is the recollection of childhood in one of its aspects, though perhaps not in other aspects.

It is the recollection of childhood innocence, as experienced in reading the literature of childhood—not Wordsworth’s glorious contact with the transcendental, but the happiness that is conjured by children’s books, or by the memory of reading children’s books, within the tender warmth of the domestic hearth. He lingers in Knife over a treasured family photo showing him as a little boy together with his young sisters examining a copy of Peter Pan. In a remarkable passage, he recalls the moment when, after the assassination attempt, and the hospitalisations, and a long stay hiding out from the paparazzi at a friend’s apartment, he returns at long last to his own home. And he is reminded of Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows and the anthropomorphic Mole, who returns from his adventures abroad to his own beloved mole hole, which is home, fragrant with the glories of everything that is quaint, contented, and reassuring. Rushdie writes, “Now, as my front door closed behind me, I was that contented Mole, recognising the smells of the place, my heart leaping as I saw the photograph of myself and my sisters reading Peter Pan that hung above the fireplace….”

One after another of Rushdie’s books conjures a happiness along those lines—the happiness of a child smitten with the splendour of books and their marvellous stories, as appreciated within the universe of one’s own domestic mole hole. This is a happiness of burbling joy, suitable for his verbal acrobatics. Sometimes the burbling drifts into zones of the not-always happy unconscious. The greatest scene that he has ever written—the scene that, unfortunately, has led to the many disasters that have befallen him—is the sequence in The Satanic Verses in which his character Gibreel dreams deliriously of a world roughly parallel in crazily distorted ways to the world that Islamist fanatics conjure, where the pieties of the Koran intermingle grotesquely with the most dreadful of cruelties and upside-down moral transgressions. Only, some aspect of the delirium remains quaint in spite of everything. It is the delirium of an addled young immigrant in England who is having a hard time of it, and whose deep-sleep unconscious has gone on something very close to a blasphemous tear, but who is nonetheless quite a nice young man and could almost be presentable, if only his luck with women and his sanity would take a turn for the better (which does not happen).

Rushdie’s cult of childlike innocence sometimes makes for a strange placidity in his male-female dramas, as if the conflicts and attractions of love could be reduced to a gift-wrapped package, suitable for presentation to a little child. In Knife, husband and wife confer, post-attack:

How are you feeling today, honey. How are you doing, darling. This is Day Four after our lives were changed forever.

You know. . . it’s up and down. But I am surrounded by the ones I love. Primarily you. So I can do it.

We’re going to come through this. We have more stories to tell. And what we have is the greatest story, which is love.

That’s right.

Today is another good day. Another good day for us, together.

It’s thanks to you. You’re doing all the work.

You did the biggest thing. You didn’t die.

My poor Ralph Lauren suit.

We’re going to get you another one. We’ll walk right into that Ralph Lauren store and say, Give this man a suit.

I think they just might give me one.

How is your hand, darling?

It’s heavy. It feels like I have an extra hand hanging off my arm.

I love you. We’re going to come through this.

I love you too.

But Rushdie is not entirely wrong to see a defiant dignity in this sort of thing. More than thirty years of getting mauled by the ayatollah and by everybody who has agreed to be influenced by the ayatollah, which is a lot of people, followed by an actual devastating attack, have left him, as he is proud to announce, unchanged. To the ayatollah, Rushdie says: No. The pre-fatwa Rushdie is the post-fatwa Rushdie. And so, if the urge comes upon him to write “I wuv you” baby-talk, he will not be stopped. There is an art in this, too—or, at least, sometimes there is. Gabriel García Márquez composed more than a few passages in a baby-talk tone, and he did this on the same logic that is Rushdie’s, which is the belief that memories of childhood emotion are a proper starting point for anyone who wants to arrive at a wide-awake consciousness—the childhood starting point that allows a writer to identify every cruelty and insanity that is the opposite of childlike. The naive and the cracked are the foreground and the landscape for García Márquez and Rushdie alike. But it is also true that one word too much of baby-talk dialogue is more than too much, which means that each new book by Rushdie teeters on the edge of just right and too much.

In one passage of Knife he reverts to his characteristic ebullience. He tells us that, when he regained consciousness, he saw visions:

They were architectural. I saw majestic palaces and other grand edifices that were all built out of alphabets. The building blocks of these fantastic structures were letters, as if the world was words, created out of the same basic material as language, and poetry. There was no essential difference between things made out of letters and stories, which were made of the same stuff.

That is Rushdie’s notion of the cosmos, pretty much.

Something like Hagia Sophia in Istanbul was manifested to me by my unsettled brain, and the Alhambra, and Versailles; like Fatehpur Sikri and the Agra Red Fort and the Lake Palace of Udaipur; but also a darker vision of El Escorial in Spain, menacing, puritanical, a nightmare rather than a dream. When I looked closely the alphabets were always present, mirror-gleaming alphabets and grim letters of stone, brick alphabets and treasure-letters of diamond and gold. After a while I understood that my eyes were closed. I was still thinking of my eyes in the plural then.

But apart from that one visionary and heartbreaking passage and perhaps a few other fleeting lines here and there, Knife is, by Rushdie’s standards, a terse book, only two hundred pages, and mostly tethered to the ground. He tells us that, as a consequence of the attack, he lost a lot of weight; and you do feel, as you turn the pages, that he is a thinner man. He devotes a chapter to imagining a jailhouse verbal confrontation with his assailant, whom he calls “A.” for “assailant,” without deigning to address the young man by name. But A. remains morose and sullen during the confrontation, and Rushdie remains fairly morose himself, and, even if Rushdie and A. do hate each other, hatred does not light up the sky. And yet, the terse and modest tone serves a purpose. The geysers of enthusiasm and marvellous images that have always lit up his pages subside in Knife, and, by doing so, they allow the pathos of his extraordinary career to stand out more clearly—this career that has somehow stretched across an immense horizon of the playful, the horrible, the tragic, and (I apologise for invoking Hegel) the world-historical.

Rushdie’s Moral Heroism

The attempt on the great writer’s life illustrates the dedication with which fanatics pursue the objects of their hatred.

Rushdie is, after all, a man who, through feats of talent or strokes of good and bad luck, has found himself not once but twice writing a book that defined our era. The first time he did this was in Midnight’s Children, when he identified himself with the independence of India and, in doing so, ended up producing a classic novel of decolonisation. If he had stopped writing novels after that one book, and two or three of its successors, he would be even now a favourite son of a certain literary Left, which deems itself decolonisation’s loyal ally and sees a virtue in denouncing any and every attempt to draw invidious distinctions between decolonisation’s admirable side and any other side.

But Rushdie’s own impulse was, in fact, to draw distinctions. In Knife, he says, in a remark that everyone can appreciate, “Truthfully I would be happy never to speak about The Satanic Verses again. My poor maligned book.” But a word ought to be put in for the poor maligned book. Its scandalous passages showed something that I think had never been shown quite so vigorously or technicolourfully before, or only rarely, which was the Islamist fanaticism that was just then—in the late 1980s—beginning to wreak untold miseries on one province after another of the no-longer colonised world. To show this to the world may not have been Rushdie’s intention, but it was his achievement. And he has had the misfortune of illuminating in his life, and not just in his books, those two global developments, the triumph in many parts of the world of a liberating decolonisation, and the counter-triumph in some of those same parts of an anti-liberating Islamism.

His earlier memoir, Joseph Anton, back in 2012, already told his own story against the backdrop of those two developments, and it did so largely in his chosen tone of rhapsodic happiness, even if the experiences he recounted were anything but happy. And now the same story has had to be once again his theme. Only, this time he has had to write the story in a tone of post-happiness, straitened and relatively austere. It is the tone of a man who may be unbowed, but is gravely wounded. The post-happy tone makes Knife a moving book, more affecting, I think, than anything else he has written—a moving book in itself, that is. But Knife is moving also because it carves a scar retroactively and even prospectively across the whole of Rushdie’s literary career, past and future.