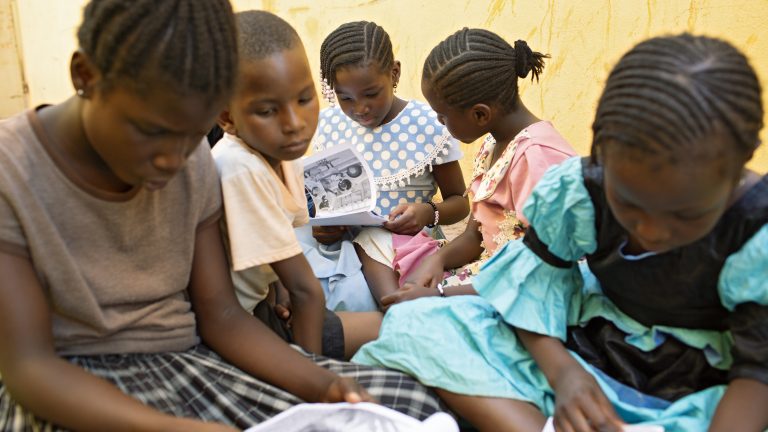

For the past six months, Alou Dembele, a 27-year-old engineer and teacher, has spent his afternoons reading storybooks with children in the courtyard of a community school in Mali’s capital city, Bamako. The books are written in Bambara — Mali’s most widely spoken language — and include colorful pictures and stories based on local culture. Dembele has over 100 Bambara books to pick from — an unimaginable educational resource just a year ago.

From 1960 to 2023, French was Mali’s official language. But in June last year, the military government replaced it in favor of 13 local languages, creating a desperate need for new educational materials.

Artificial intelligence came to the rescue: RobotsMali, a government-backed initiative, used tools like ChatGPT, Google Translate, and free-to-use image-maker Playground to create a pool of 107 books in Bambara in less than a year. Volunteer teachers, like Dembele, distribute them through after-school classes. Within a year, the books have reached over 300 elementary school kids, according to RobotsMali’s co-founder, Michael Leventhal. They are not only helping bridge the gap created after French was dropped but could also be effective in helping children learn better, experts told Rest of World.

“Artificial intelligence will help a lot in making sure no language is marginalized. So, I hope RobotsMali will be reinforced and become the center of AI utilization for improving teaching in our national languages,” said Assétou Founé Samake, a former Malian minister of higher education and research. “We don’t want languages to be marginalized, because every language contains a culture [and] knowledge that we must not lose.” Samake was closely involved in the push to replace French with local languages as the mode of school education in Mali for the past several years.

RobotsMali was launched in 2017 by Leventhal, an American machine-learning expert, and Malian education advocate Seydou Katikon. The idea was to give children the opportunity to learn about robotics using affordable hardware. The initiative — backed by Mali’s education ministry, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Google, UNESCO, and the World Bank — has so far trained more than 9,000 students in STEM, robotics, and AI, according to its website.

A team of five people from RobotsMali started developing books in Bambara in 2023. They generated stories using ChatGPT, and would then translate them into Bambara with Google Translate. (Incidentally, RobotsMali helped create the first French-to-Bambara machine-learning data set in 2020). The team then carefully curated a set of locally relevant images that matched the stories using Playground, an AI image generator tool.

During the process of producing the books, the group paid close attention to prompts that tend to give Eurocentric results or stereotype Africans, Leventhal told Rest of World.

“While generative AI is very good at depicting the physical characteristics of African people, we routinely encountered difficulties with idealized images of human bodies, unfamiliar and often inappropriate dress, and environments reflecting Euro norms that bore no resemblance to typical African settings,” Leventhal said via text. “Without adjusting prompts, African men and women most often are hypersexualized — men depicted as shirtless with bulging muscles, women in scanty clothing with heaving bosoms … even when the scene depicts, say, a family scene. We use a lot of negative prompts to remove these characteristics such as (NOT) sexy or showing bare skin.”

In October 2023, the Malian education ministry’s Department of Non-Formal Education and National Languages discovered RobotsMali’s work, and proposed a collaboration. Now, RobotsMali trains the department’s workers to create books by themselves.

In February, when Rest of World visited RobotsMali’s office in Bamako, two government officials were correcting translations of stories and generating AI images of an African woman holding fruit for a children’s storybook in Minyanka, another local language.

Besides offering a replacement for French texts, RobotsMali’s books help teachers be more effective in class. “When you have to explain a complex concept to the students in French, which isn’t even their native language, sometimes it takes them a long time to understand,” Dembele said. “If I say ‘Two plus two’ to a child in the second grade, he has to think a lot … But if I say, ‘Ni ye fila fara fila kan,’ he will give me the answer right away.”

In Mali, 40%–60% of students drop out of school in the first six years, but that would greatly reduce if students learned in their mother tongue first, according to Issiaka Ballo, a professor at the Bamako University of Arts and Sciences.

“A child who leaves home where he speaks Bambara, you bring him into an environment where we don’t speak Bambara to him — we speak to him in French, a foreign language,” Ballo, who has created digital resources in Bambara, told Rest of World. “What will this do to him? He will be disoriented because his linguistic environment does not allow him to understand what you are saying.” Ballo has worked with RobotsMali to bring Bambara to Google Translate, and also translated it into Braille. The government can expedite the use of native languages in schools through the creation of proper policies, he said. Globally, there’s a growing effort from individuals and companies to use AI to either teach local languages or preserve endangered ones. In Brazil, IBM is funding a project to help preserve and expand the use of Indigenous languages in the country with AI tools. In New Zealand, Reobot, a chatbot, uses AI to help people learn Maori. Masakhane, an open-source cross-continental AI project, is trying to preserve African languages and make them accessible on the internet.

RobotsMali’s AI books project is not just about preserving languages but also about owning the narrative and preserving the right to internet access, Leventhal said. He believes generative AI will have a big impact on the way people search for information online, but said “the problem is that it’s only supported in a small number of languages — that basically serves the elite population of the world.”

Abdoulaye Nimaga, a 13-year-old ninth grader from Bamako, told Rest of World he is worried that learning in a local language will limit his access to global opportunities. “I saw the results in my daily life — they taught us a lot of things,” he said. “It’s just in Mali that we speak Bambara. So if you base yourself on just Bambara, when you go somewhere else, you won’t be able to understand anything.”

Dembele, however, said that teaching kids in their native language first is important, because it helps them better understand what they know about the world around them, especially given the ongoing violence, insurgency, and attacks on schools in Mali. He believes better education will solve these problems. “We have a bright future if we promote our languages. This is sure. I don’t have any doubt,” he said.

![Book Writing Tips (How to get ISBN and Copyright for your book?) [hindi video] Book Writing Tips (How to get ISBN and Copyright for your book?) [hindi video]](https://www.todaysauthormagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/1730832624_maxresdefault-120x86.jpg)