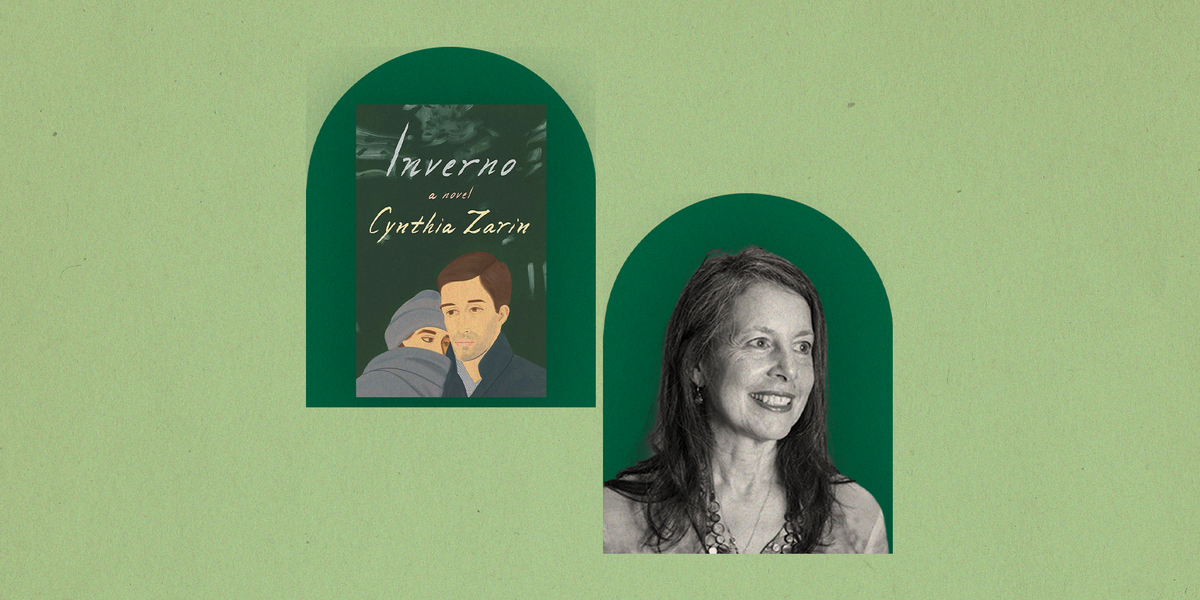

Cynthia Zarin has worked in just about every version of a literary career possible. She’s published five collections of poetry, teaches writing at Yale, contributed to The New Yorker for years, published children’s books she wrote when her own kids were young, written criticism, and even seen one of her pieces turned into a ballet. This year, Zarin is publishing her first novel, Inverno. When I mention how all-encompassing that résumé sounds, Zarin jokes that it’s not every version of a literary career since she hasn’t written any theater. My guess is that this comes with an unstated “yet.”

Inverno is an odd little novel. For most of the book, Caroline is waiting for Alastair in a park he’d once lingered in as a child. The narration follows Caroline’s memories of their winding, years-long, intense relationship, though sometimes it pulls from Alastair’s memories as well. The story is told in decades and moments that feel like something between poetry and memory. Their collective memories are full of deep references to movies, music, and Scandinavian fairy tales, among other things. In one section, Caroline thinks through the process of using a phone booth in Melville-ish detail.

Shondaland sat down with Zarin to talk about the lines between genres, the impossibility of communication, and the inevitability of making up your interlocutor.

SHELBI POLK: Where did this book come from?

CYNTHIA ZARIN: Well, I had written prose for children. When my children were small, I wrote a lot of picture books. And I’d written lots and lots and lots of prose for The New Yorker. And then, personal essays came out of that. But I was not somebody who sat around thinking, “Oh, I want to write a novel,” or had a lot of novels in a drawer. It simply didn’t occur to me that I would do such a thing. But I started writing a letter, or a kind of letter, to somebody, and I realized, as I was writing it, that I wasn’t really writing a letter. I was making up a lot of things and telling stories, a little bit like Scheherazade, and they kept both of us amused. And then, it became clear I wasn’t probably going to show him most of the letter. And it just kind of took on a life of its own.

And then at a certain point, I stopped. I had a lot of words. And, you know, I’ve been a working writer since I was 22 years old. And to me, when you have words, you have to do something with them. I’m a sort of old-style GrubStreet writer. So, what was I going to do with all these words? John Updike used to say he never wrote anything that he didn’t envision in 12-point type. I spent a number of years, many years, writing up bits of it and showing it to friends. Once at a poetry reading, I read a couple of pages out loud just to see what it felt like. And everyone would say, “It’s a lot of writing, but is it a book?” I kept trying to put it together, and then my great friend — brilliant and gifted and in many, many ways — Leanne Shapton said, “Why don’t you just take it apart?” Instead of trying to put it together, take it all apart. So, I took it all apart, and then it was much clearer how to put it together.

SP: It’s so fascinating that Inverno came from a kind of — I don’t want to call your letter a failed communication — but this book is so much about miscommunicating and not saying the things that you need to say.

CZ: Nobody has said that before! As you may know, I teach mainly nonfiction, prose, and poetry. But one of the things that we talk about in class often about poems is how a poem is often something that you write to someone whom you can’t communicate with in any other way. Someone who you feel might not be listening. All of English literature is really about that. So, it’s interesting that you would pick up on that. I’ll have to think about that. Thank you.

SP: The narrative felt very true to life, remembering all these different images and circumstances coming back in a rush. I’m sure there was some careful organization behind the novel, but the result felt very fluid. When you say you took it apart, was it a more straightforward narrative at one point? And how did you organize all of these references?

CZ: It was always very circular. Just the way I think we all think about our lives, whether it’s about our romances or our childhoods or really anything, we have certain images that come back. If I was to say, “What’s your most important summer memory?” You know what it is, and you don’t have 10 of them. And we return, and of course as we return, we embellish those memories and change them. You know, we’re very conservative when we think about the future, but we are endlessly inventive when we think about the past, right? Caroline and Alastair have a relationship that gets tracked over many years but has a very big gap. There were things that happened right at the beginning, like the sledding or taking pictures of the boat, and then later on, when she goes to see him and waits in the snow. These are things that she will just keep coming back to as emblematic. I’ve been really astonished about how many people who’ve read it, you know, of all different ages and identifications. I think everyone has an Alastair in their lives somewhere.

SP: It certainly is a familiar frustration. So — sorry, this might be one of the main theses you teach about — but why isn’t this poetry?

CZ: It’s interesting that you asked that because I’m teaching a class at Yale, and it’s only the second time I’ve taught it. So, you know, it’s still fresh. It’s an advanced class called “Writing Across Literary Genres.” The students come in with an idea, and it can be, I don’t know, eyesight, this pair of glasses. It can’t be some big historical concept. Someone in the class, for example, is writing about Mary Magdalene, and somebody else is writing about spying. And they write an essay, a poem, a short fiction, and a scene in a play. And then, for their final project, they expand it. And it’s been so interesting. We keep saying it’s more about what is the achievement in a form versus that one is better than the other. It’s more that you can just do different things. A friend of mine and I were having breakfast the other day, the novelist Jane Mendelsohn, and we were actually talking about this. I said, “A poem is a little bit like you go out into a field, and you pitch a tent, and you wait for a lightning to strike.” When you’re writing a novel, you may go to the same field, but you’re building a house, building the town around the house. Even if you never see it, it appears in that way. And then, when you write an essay, it starts fairly often just within a thought or an idea that you tease out in a more discursive way.

SP: Sure, it’s not strict literary realism in that, like, Person A did a thing that led Person B to feel this way, which led to C, right? But as I mentioned, it still feels very real and familiar — like memories but in a poetic way.

CZ: Right? My joke with my publisher is let’s not call this a poet’s novel — nobody’s going to want to read it. But I mean, I think that order — this happens, which makes somebody do that, which makes something else happen — is it really ever that straightforward? Grace Paley, who everyone should read, always would say there’s a story, but there has to be the second story. What’s driving the first story?

SP: So, you have Inverno and your New and Selected Poems coming out this year. What a fun spread! It must be such a great feeling to have enough work to have a New and Selected Poems.

CZ: It makes me feel like a very old lady. My longtime editor said, “I think we should do this.” I was like, “Oh, my God.” But I guess I started publishing poems in magazines when I was about 19. And then, my first book was accepted when I was about 25. So, I started early, but it’s very exciting. My first husband is a painter, and his work is on the covers of my first books, The Swordfish Tooth and Fire Lyric. And now, a painting by our daughter is on the cover of the New and Selected Poems. So, that is very nice.

SP: How gorgeous. That’s really special.

I’m very curious: Is your poetry often about characters? Was it a jump to go from writing poetry to writing about characters?

CZ: Well, I think that’s a really interesting question. Because I think that the persona that is in one’s writing is a creative persona, whether it’s the poetic voice, a reporting voice, personal essays. And then, fiction creates a kind of diction. To some degree, it’s a self-portrait, but it is created out of language, you know? I think most writers, we’re using a means of expression to create a tone. So, I think I’ve been pretty much doing it all along. But I think one’s diction changes over time. I’m always very, very conscious of punctuation. I was very conscious about the pacing of the sentences of Inverno. I wanted them to have a kind of headlong quality but also be very restrained. Caroline may be a little bit mad, but she’s not sloppy. So, I wanted the sentences to have the kind of diction that I imagined her using as she spoke to herself or to the person to whom she’s telling the story.

SP: She is so deliberate in her speech, while making some very less than deliberate choices or actions here. Would it be spoiling things to ask who, exactly, is speaking to whom?

CZ: Well, if you were to chart it, there is an omniscient narrator. But that omniscient, as I realized later, you know, is speaking in the first person. And so, the story is being told by Caroline. She’s telling it to another person, who comments occasionally and makes fun of her occasionally. She knows that he’s going to tell her, “Well, that’s getting a little boring,” or “What happened to Caroline? You left her in the snow.” So, she’s speaking to him, and there’s sort of a level of the real, omniscient narrator telling a story about these two people, mainly from Caroline’s point of view but somewhat from Alastair’s.

SP: I think my theory was she was telling it to herself, so I’m glad to hear that she gets to share this with somebody else.

CZ: Well, I think that’s a very interesting thing to say because, of course, she is making up the person who she’s telling it to. As we make up everybody in our lives, to some degree, right?

I mean, when you’re talking to anyone. It doesn’t have to be romantic. If you’re talking to your mother in your head, is it the mother that your mother would recognize? Or is it your mother? We always create the people around us. And hopefully, sometimes, we listen to what they’re actually saying, but how often does that really occur?

SP: Which does loop us all the way back around to these miscommunications and these gaps even in the most well-intentioned conversations, right?

CZ: Yes, and now we have so many ways to communicate. I tried to explore this a little bit in the novel. Now, we have texting, we have phone calls, we have Zoom. We have the internet and email and chat and Slack, and things I’m sure I haven’t even heard of. So, we have so many ways to communicate, but are we actually communicating anymore? I don’t know. I don’t think so.

Shelbi Polk is a Durham, North Carolina, based writer who just might read too much. Find her online at @shelbipolk on Twitter.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY